Shintaro Kago is a difficult creator to pin down. Notoriously known as a man of few words, he prefers to let his work speak for itself, but what it's trying to say exactly, is...well, to say up to interpretation is an understatement. Occasionally lumped in with Junji Ito in terms of art style and "horror" content, sometimes referred to as an ero-guro (erotic-gore) mangaka, and pretentiously referred to as specializing in "fashionable paranoia" by Western markets, he seems to prefer to use the word "kisou" (bizarre) to describe his body of work. But what defines a bizarre manga? Well, let's take Demntia 21 as a prime (albeit relatively tame) example.

When I saw solicits for a work by Shintaro Kago, and published by prestigous indie publisher Fantagraphics Books, I was honestly surprised; Fakku Books had published a Shintaro Kago collection titled Super Dimensional Love Gun earlier in 2018, a wide ranging collection of Kago's short stories that didn't shy away from some of the more graphic content he's known for (for example, White String). This was the first of Kago's works to be published in the US, and with Dementia 21 hot on its heels, and having not read it before myself, I wasn't sure if I should expect more in the same graphic, shocking vein or not. Not that I would have minded, I thorougly enjoyed SDLG, it epitomized what I love about Kago's art: his graphic, gross-out humor with erotic subtexts.

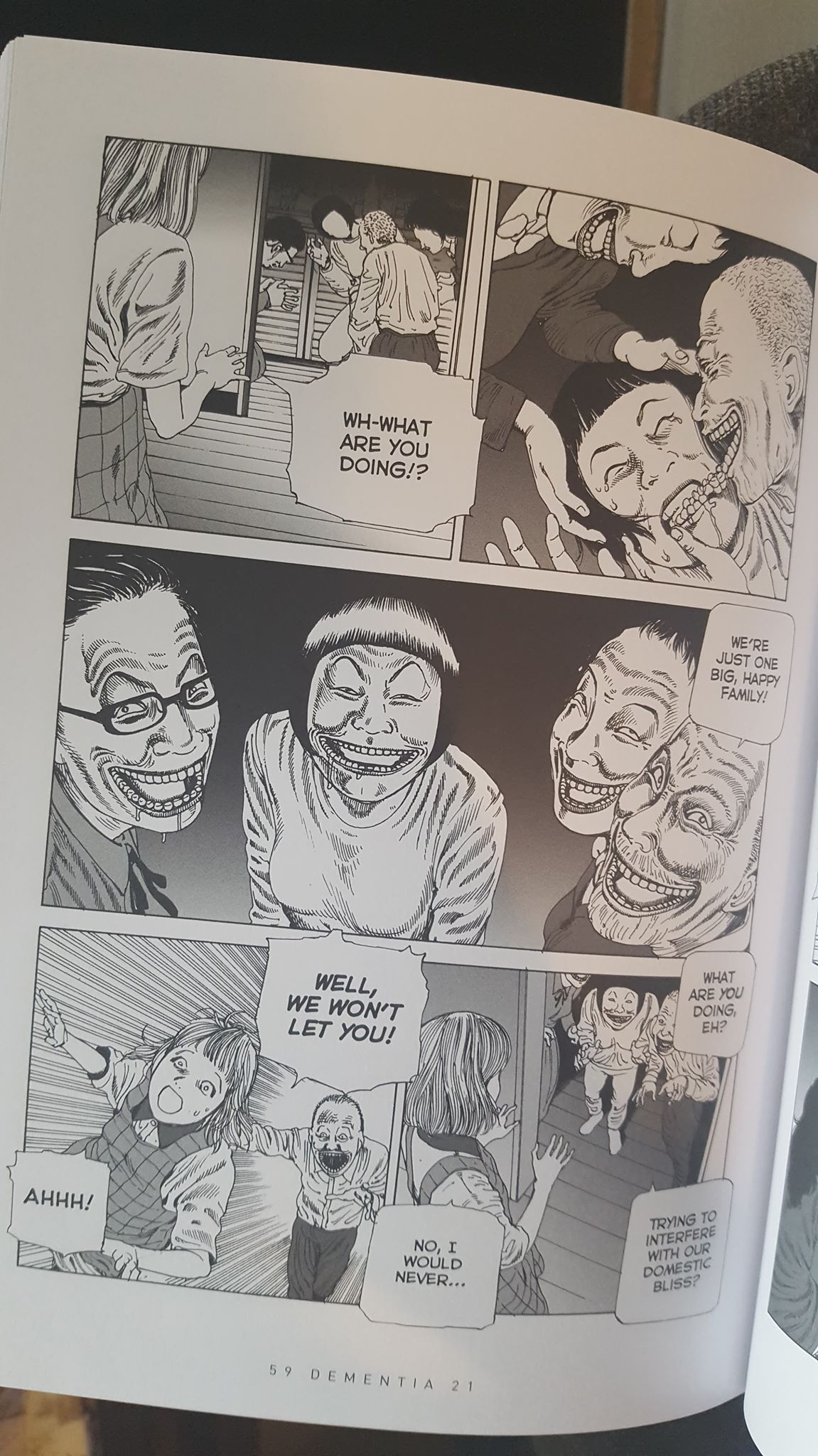

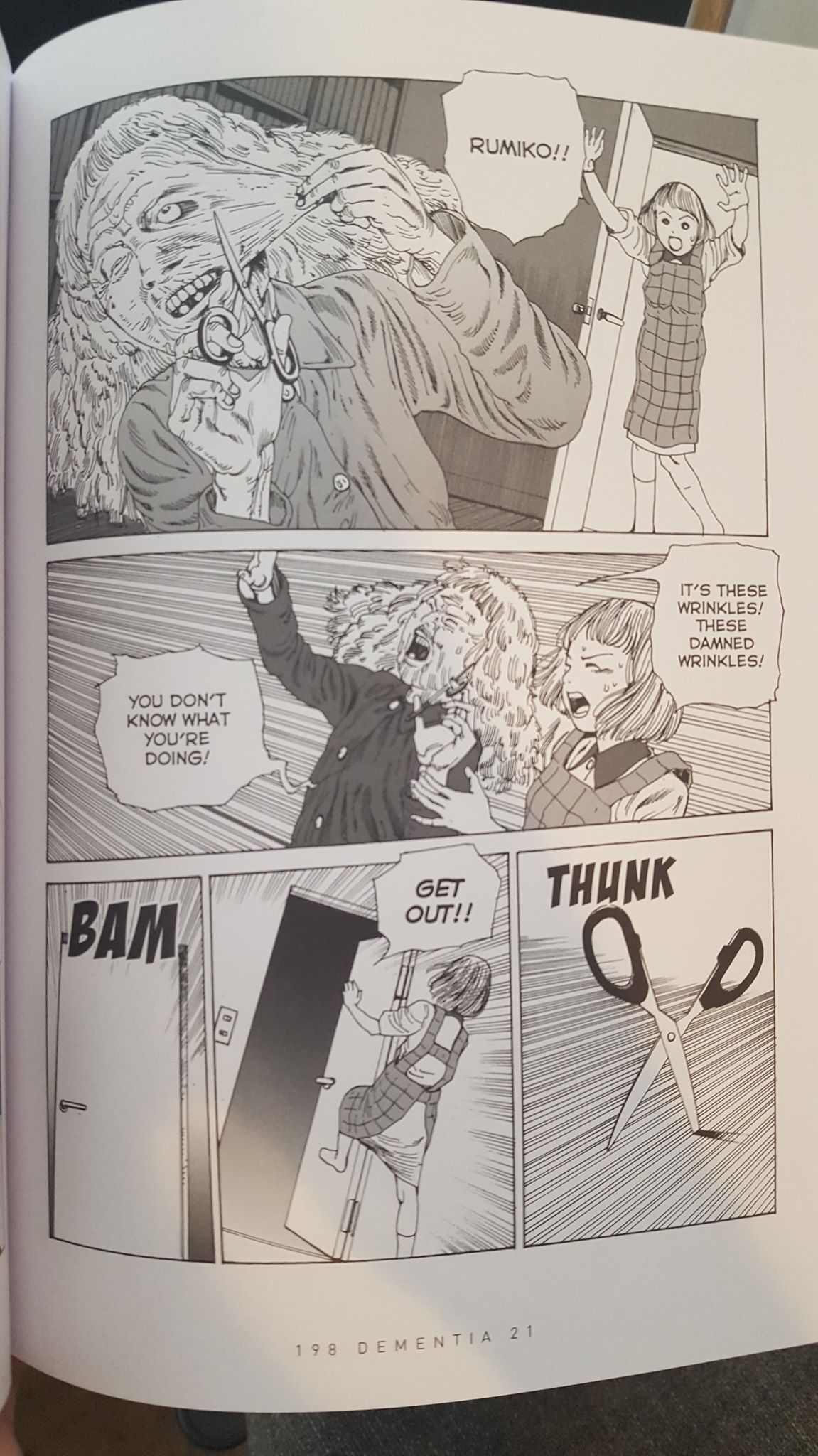

Dementia 21 is significantly milder fare, but no less enjoyable. Kago's art is still in top form, highly detailed and deceptively generic; and his ability to tell the most outrageous of stories is on display. Dementia 21 is about Yukie Sakai, a young home health aide eager to help her elderly clients, but what seems like a simple, straightforward job quickly turns into a series of surreal adventures that put her wits to the test. Initially following a semi-narrative structure where Yukie's coworkers are attempting to sabotage her flawless record by sending her to impossible (and dangerous) jobs, this is quickly abandoned in favor of tales of Yukie's misadventures with the elderly patients she cares for. It's almost an Alice in Wonderland type tale, if instead of Mad Hatters and March Hares, Yukie's world is populated with mind controlling dentures with the ability to self-replicate, incredible psychic powers, and never-ending extension cords.

As someone who is not Japanese and whose knowledge of Japanese culture is derived almost entirely from media consumed, the book does seem to me to be "about" (if something so anecdotal and intentionally over the top can be said to be "about" anything) Japan's fear of old age. This makes a lot of sense when we consider their population, which is shrinking in the face of longer life expectancies and declining birth rates; a similar phenomena is occuring here in the West but at a far slower rate. In Japan, there are more jobs than there are bodies to fill them, threatening rural communities with extinction and contributing to huge strain on the labor force, as well as tons of other problems (here's an article if you're interested in reading about that kind of thing). However the book isn't held back by the culture of its creator, as aging and death is a fear that transcends all of us, as many of the horrors of this book will likely be recognizable to any reader. But for every story that reflects a common fear of aging, there is the mirror image of the burden that having an older family member represents, the unrealized dreams and lives set aside in performing the expected good duty of caring for those that raised you, a life I saw my own father live and that has profoundly affected his relationships and choices ever since, and has affected how I view the approaching retirement of my own parents, for better or worse.

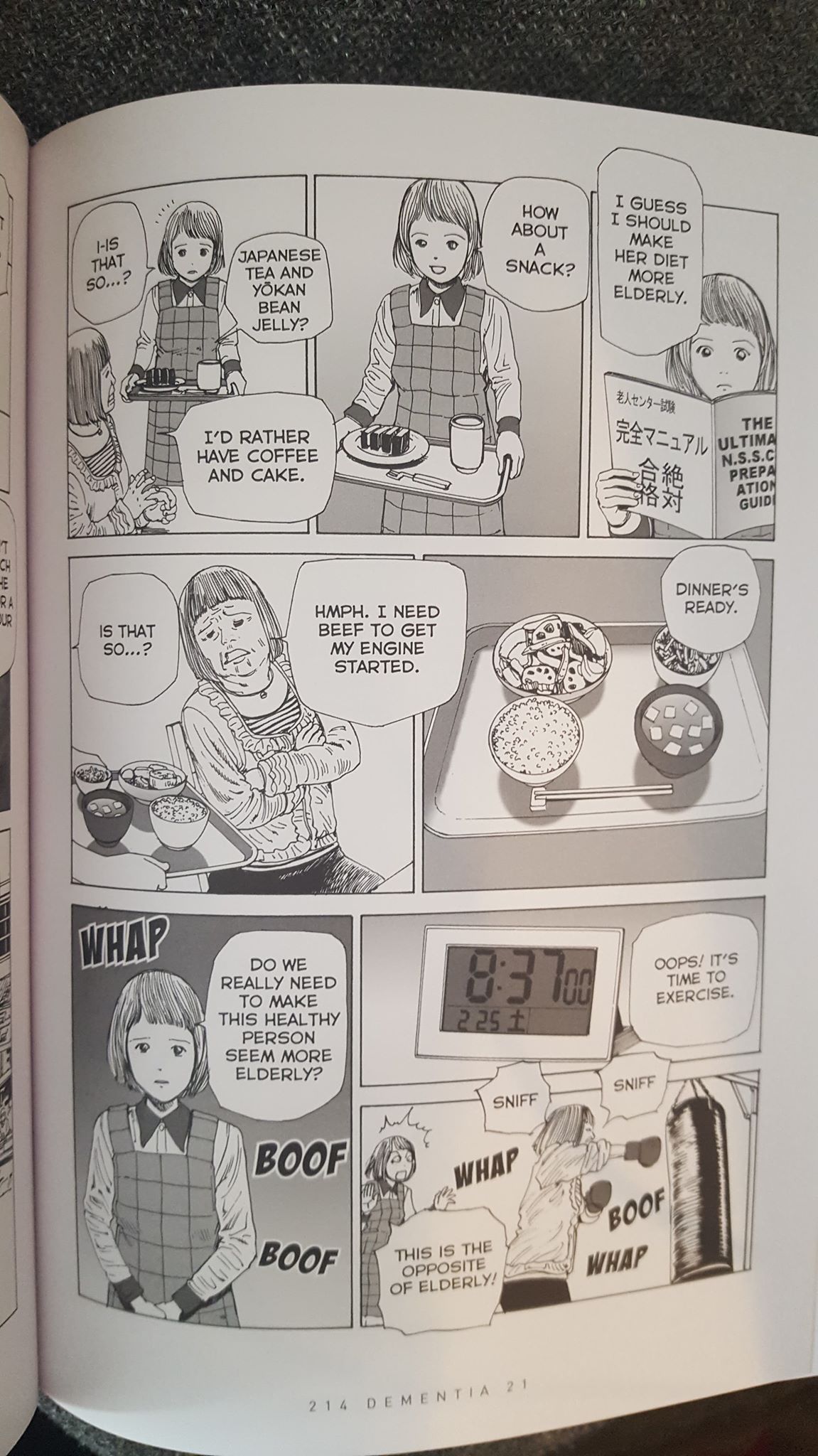

One story that particularly stuck out to me was the one contained in chapter 14, in which Yukie is tasked with helping one of her clients, Nanae Matsushima, study for a National Standardized Senior Citizen Exam by the Matsushima's daughter-in-law. Encompassing mental and physical components of all types, those that pass the exam are eligible for top notch free health care, exemption from taxes and fees, and more. The problem is that Nanae is in great health, and has an upbeat, youthful spirit. Under pressure from Matsushima's daughter-in-law, Yukie warily sets about destroying the health and happiness of her patient, against her better judgement and professional morals. The twist at the end, of course, is that Nanae does so well in the exam that she reaches the final test, which is to see how well she can fulfill the old-lady stereotype of hectoring her daughter-in-law into insanity (the age old tradition of difficult to please mothers-in-law, particularly widespread in Japan, is seen time and again in this book, with one entire story dedicated to the most impossible to please woman you could possibly imagine).

Dementia 21 breaks genres, managing to dabble a bit with zombies (if not strictly undead ones), aliens, the aforementioned psychic powers, neverending loops to be trapped in, and even tokusatsu, the live action superhero genre that spawned Ultraman, The Power Rangers, and inspired anime superhero teams such as Sailor Moon for years to come. There are no boundaries and taboos in Kago's work, even down to the squeamish topic of when to pull the plug on a suffering loved one, and the death penalty. If you're already familiar with Kago's more in-your-face stories and/or art, Dementia 21 will provide a familiar but fresh look at a different side of the creator; and if you're not familiar, I think this could be a good introduction to his art style and storytelling methods, without going feet-first into girls sneezing their skeletons out of their bodies and a heads made up of mouths. You know, to see if you're into that kind of thing.